If we wish a houseplant to flourish, we provide it with water, nutrients, and light. We set it near a window. But should we wish the same for ourselves, for those we love, and for humanity in general, what are the counterparts of those necessary conditions? What practices, activities, and qualities of mind contribute to human flourishing?

In his timely new book The House We Live In: Virtue, Wisdom, and Pluralism, an ambitious endeavor to forge a pragmatic, “flourishing-based” ethic for our pluralistic, multicultural society, the Zen priest and psychologist Seth Zuihō Segall identifies multiple “domains of flourishing.” These include “relationships,” “accomplishment, “aesthetics,” social acceptance, “meaning,” and “whole-heartedness.” Exploring the last of those “domains,” Segall invokes a practice from the Soto Zen tradition.

Known as menmitsu-no-kafu and translated by Segall as “whole-heartedness,” this practice might most simply be characterized as giving full attention to whatever one is doing, be it driving, chopping vegetables, or listening to a friend. But, as Segall explains, the practice also entails “exquisite, careful, considerate, intimate, warm-hearted, continuous attention to detail.” And, in contrast to those meditative practices prescribed for self-pacification and self-improvement, menmitsu is directed outward rather than inward: toward the benefit of others rather than oneself.

Traditionally, menmitsu is taught by Soto Zen instructors and practiced within the confines of a temple or Zen center. There, ordained monastics and committed Zen students learn to embody menmitsu as they engage in their everyday activities: “donning their robes, sweeping the walkways, refolding their bowing cloths, assembling and disassembling their eating bowls, lighting incense, and so on.” All are to be done with “exacting, meticulous attentiveness.”

As Segall readily concedes, not all of us are “called to the same degree of attentiveness” or prepared to practice menmitsu in every aspect of our lives. At the same time, Segall suggests, “we could do well to take a page” from this integral dimension of Zen practice. Practiced in excess, menmitsu can look like OCD and feel like hypervigilance—and, if one is married, drive one’s spouse to distraction. But, practiced thoughtfully and with moderation, menmitsu can indeed enhance our lives and those of others around us.

For my own part, I have found it most productive to apply the principle of menmitsu primarily to those daily activities I most value and enjoy, including formal Zen meditation; studying and practicing the classical guitar; reading and re-reading great literary works; cooking; conversing with friends and family; and, most centrally, the craft and art of writing, which can embody menmitsu in at least three ways.

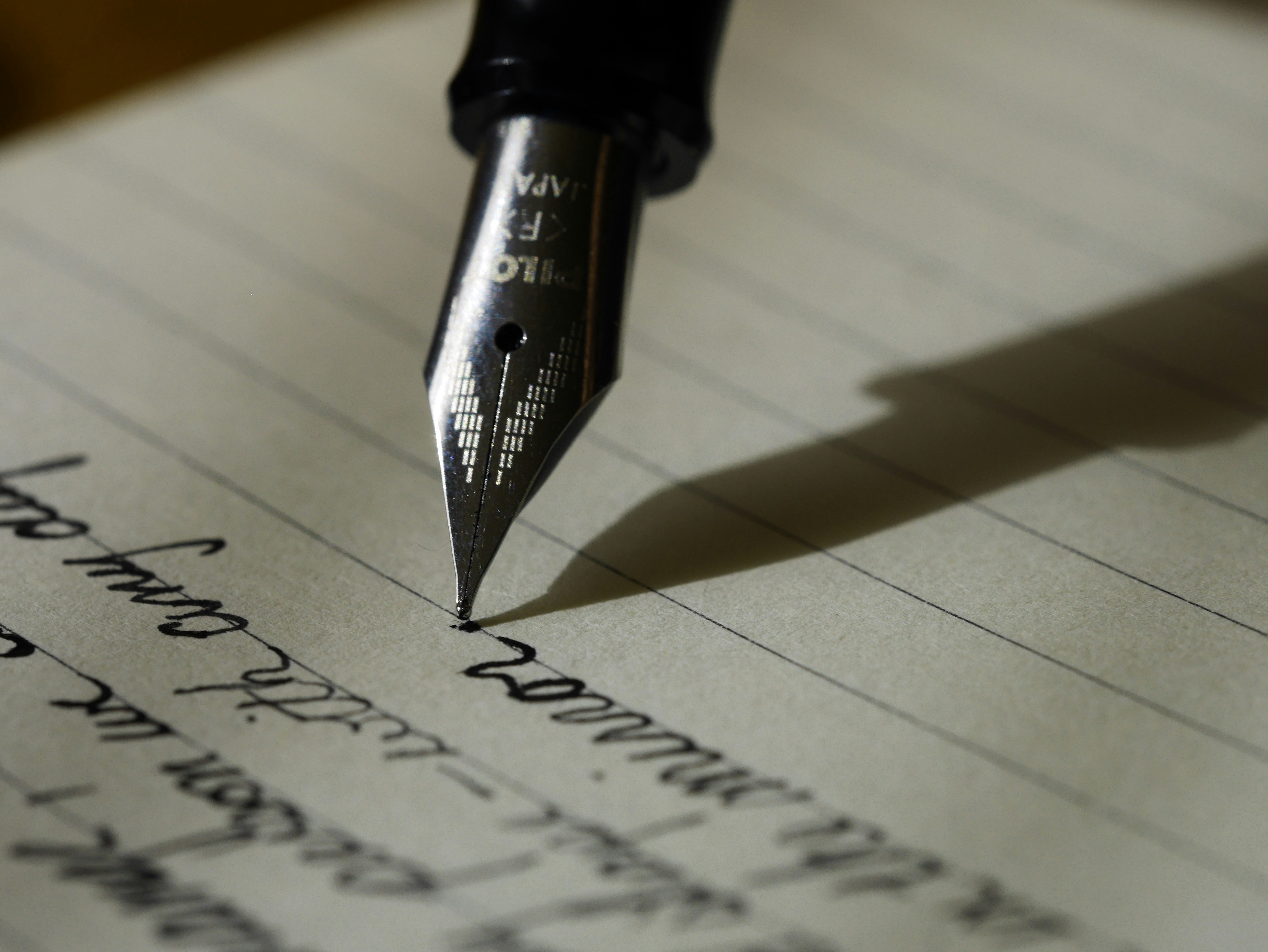

To begin with, the practice of literary menmitsu can begin with the choice to write with a pen or pencil rather than a keyboard. However archaic handwriting has become in the age of the iPad, writing by hand is not only a sensuous, intimate way of “getting the better of words,” as T.S. Eliot once put it. Handwriting also promotes precision of diction and meticulous attention to detail. “Writing maketh the exact man,” wrote Francis Bacon. And if that maxim is true of writing in general, it is even more so with respect to writing, slowly and deliberately, by hand. For decades, I required students in my literature courses to write daily précis and responses in their own hands on 4 x 6” index cards, as a way of precisely comprehending the poems and stories they were reading and forming their own interpretations. I was seldom disappointed.

Second, I have found that scrupulous observance of the time-honored conventions of English grammar, rhetoric, and usage sorts well with the practice of menmitsu. Evolved over many centuries and exemplified by such masters of English prose as Jonathan Swift, George Orwell, and Scott Russell Sanders, those conventions promote clarity, concision, eloquence, and force. Beyond the basic “rules” taught in English 101—the avoidance of dangling modifiers, comma splices, faulty parallelisms, and the like—literary menmitsu can be practiced by observing such fine points of usage as the difference between “anxious” and “eager” and such grammatical details as the use of the possessive pronoun before a gerund (“his running for president” rather than “him running for president”). Fussy as such distinctions may first appear, collectively they can make the difference between lucid, accessible prose and an indigestible verbal paella.

Last and most important, literary menmitsu can be practiced by keeping one’s intended reader uppermost in mind. If I aspire to be “careful,” “considerate,” and “warm-hearted” when composing a poem or letter or essay, I can do my readers a favor by recalling the dictum attributed to Ernest Hemingway: “Easy writing makes damned hard reading.” Writing well, in my experience, is an exacting labor, not only of love but also of respect for the majesty, beauty, and ancestry of the English language and the sensibilities of one’s potential readers. A mode of “flourishing” rich in discovery, reach, and invention, the practice of literary art can also be an expression of compassion and a concrete, lasting embodiment of menmitsu.

Seth Zuiho Segall, The House We Live In: Virtue, Wisdom, and Pluralism (Equinox 2023), 102.

Photo: Aaron Burden

Early one morning not long ago, I found myself driving down NY Rte. 21 with no other car in sight. Lifting my hands from the steering wheel, I allowed my Camry to steer itself. Within seconds, it crept toward the center line, like a hungry cat stalking a chickadee. I repeated this experiment twice, and each time it yielded the same result. After 34,000 miles, I concluded, it may be time for an alignment.

Early one morning not long ago, I found myself driving down NY Rte. 21 with no other car in sight. Lifting my hands from the steering wheel, I allowed my Camry to steer itself. Within seconds, it crept toward the center line, like a hungry cat stalking a chickadee. I repeated this experiment twice, and each time it yielded the same result. After 34,000 miles, I concluded, it may be time for an alignment.